What Was It All About?

Individuals could accrue an entitlement to an earnings-related addition to their basic state pension, called the State Earnings Related Pension Scheme (SERPS). Employers could ‘contract out’ their pension schemes, which is what Lloyds did, if they provided a pension at least as good as a statutory minimum known as the Guaranteed Minimum Pension (GMP). The GMP is part of a member’s total pension.

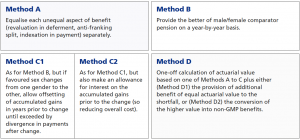

GMPs are inherently unequal and how those inequalities arise can be seen in figure 2 below. In its simplest form the issue was about how pensions, in particular GMPs, are increased under the rules of the Bank’s pension schemes.

The outcome is straightforward. The pensions of female members of the pension schemes increase at a lower rate than the pensions of male members. We argued in the High Court that was discriminatory on the grounds of sex, or, put another way, women receive less pay than men for doing the same work.

What The High Court Said

In the Lloyds Banking Group Pensions Trustee Ltd v Lloyds Bank plc and others, Mr Justice Morgan agreed with us that pension benefits – including guaranteed minimum pensions (GMPs) – are in fact “pay” under Article 157 of the Treaty of Rome and it is not lawful to pay unequal benefits between men and women.

He found that the Trustee: “is under a duty to amend the Schemes in order to equalise benefits for men and women so as to alter the result which is at present produced in relation to GMPs”.

The Court also ruled that Scheme members are entitled to receive arrears of payments due to them together with simple interest at 1% above base. The period for which beneficiaries are entitled to receive arrears of payments is governed by the rules of the Scheme. On the case of Lloyds, that’s six years from his/her claim.

What’s It Worth?

The Union’s GMP equalisation victory will affect almost all final salary pension schemes.

We believe that up to 5 million members of those schemes, the vast majority of whom are women, will benefit from GMP equalisation payments. In its submissions to the High Court, the Government’s legal team estimated that the cost of putting things right would be between £10 – £20bn.

The Next Steps

The judge will make a holding Order, effectively adjourning further proceedings until the parties have agreed the terms of the declaration the judge will be asked to make. That declaration will determine exactly how the judgement will be implemented for the LBG pension schemes.

There will a further hearing to deal with the questions relating to transfers out of the pension schemes. We expect that hearing to be in 2019.

We will keep members informed of developments through regular Newsletters.

GMPs – A Brief History Of Time

1990 – in the Barber case (17 May 1990), the European Court ruled that occupational pensions were deferred pay and, as such, schemes were required to treat men and women equally. As a result, schemes “equalised” their retirement ages, often at age 65, and adjusted their benefits accordingly.

However, as GMPs were designed to integrate with the then state pension, and the rules governing them are set out under legislation, there was some doubt as to whether Barber applied.

2010 – in her statement to Parliament on 28 January 2010, the then Pensions Minister (Angela Eagle) announced that “domestic legislation requires equalisation in respect of differences resulting from GMPs whether or not real comparators exist” (namely, a worker of the opposite sex who is being treated more favourably). Two Government consultations on possible methods for achieving this followed.

2012 – the first method consulted on would have required schemes to compare, on a year by year basis, the position of a male against a female and pay the better of the two benefits. But this method was criticised for being “administratively expensive” and resulting in better benefits for both sexes than either sex would otherwise have received. As a result, the DWP set up a working group in 2013 to consider other possibilities.

2016 – the DWP’s subsequent method involves a one-off calculation and actuarial comparison of the benefits a man and woman would have, with the greater of the two converted into an ordinary scheme benefit under the legislative facility for converting GMPs. However, the DWP made clear that trustees would not be obliged to use this method, as it did not consider providing a “safe harbour” method for achieving equalisation would be appropriate.

2016 – BTU took advice from Andrew Short QC (he represented the 3 female members at the High Court hearing) who concluded that GMPs were discriminatory and must be equalised. He said that an Employment Tribunal would conclude that the pensions of female members should be increased to the higher rate that applies to men.

2016 – August. The Union wrote to the Bank and Trustee claiming that female members are the victims of discrimination.

2016 – September. BTU put together a class action lawsuit to present to the Employment Tribunal on behalf of members that you were victims of discrimination. Members could register their details and thousands signed up.

2016 – November. The Bank, the Trustee and Union agreed jointly to refer the Union’s landmark legal action on Guaranteed Minimum Pensions (GMPs) to the High Court.

Under what’s called a ‘Part 8’ referral the High Court was to be asked to determine the answers to a series of questions on the equalisation of GMPs. Those questions were agreed by the respective legal teams.

2018 – July. The case goes before Mr. Justice Morgan in the High Court.

2018 – October. Mr. Justice Morgan says that GMPs must be equalised.

The Methods For Equalising GMPs

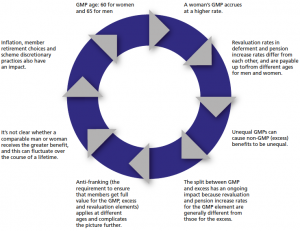

There were 4 basic methods of equalisation considered by the Court and those are set out below and in figure 2 below. In summary the key methods were as follows:

Method A

“takes each aspect of the pension calculation separately and adjusts to remove any inequality on an aspect-by-aspect approach”, on an annual basis.

As a variation on this, Method A3 would recognise any equalising increase as a non-GMP excess benefit, attracting increases under the scheme rules on this basis (as opposed to on a GMP basis) in subsequent years.

Method B

Rather like the Government’s 2012 method, this would involve a year on year calculation of and comparison between the member’s actual benefits and what he/she would have received if they were of the opposite sex. The greater of the two calculations would then form the basis of the payment to the member. Unlike Method A, this is not an element by element approach but involves a single calculation on the male and female basis.

Method C1

Uses the same initial calculation as Method B but is designed, in effect, to equalise cumulative pension paid (not pension paid each year) so as to avoid overcompensating members. So, if the annual benefit comparison reveals that the previously advantaged sex has now become the disadvantaged one (ie the two sexes have traded places), instead of applying an automatic increase to the now disadvantaged sex, the lower of the two calculations is paid “until such time as the accumulated excess prior to the switch equals the accumulated loss after the switch”.

Method C2

And this one was ultimately favoured by the judge in the Lloyds Banking Group case uses the same calculation except that interest is allowed for “when comparing accumulated gains and losses in the case of a switch in calculation from one sex to the other”.

Method D1

This would involve a one-off actuarial calculation of the future rights to benefits of male and female comparators, with any difference paid to the disadvantaged members as additional pension. As a variation on this, Method D2 would involve using the GMP conversion legislation and providing “a pension which converts GMP structures into an alternative format (for example in line with non-GMP benefits) and is of equal actuarial value to the larger of the compared values”. This method is akin to the Government’s 2016 proposals, although the judgment notes that there may be differences in detail.

(It was also noted that versions of Method D have been used when schemes have been buying out benefits with an insurer although, in those circumstances, “the commercial imperative to achieve risk transfer in the buy-out will outweigh the risks of the equalisation approach subsequently being deemed inadequate”.)

The vast majority of those pension scheme members are female and most of those will receive pension scheme increases that are lower than male members of staff.

The Issues Left Unanswered

Having concluded that the obligations in relation to GMP equalisation apply to benefits accrued in other schemes post-Barber which have been transferred in to the Schemes, the judge stopped short of reaching any conclusions about the position on transfers out. In doing so, he stated that “it might be undesirable to deal with the arguments at a high level of generality and without regard to specific facts”.

Another issue left unanswered was whether a different equalisation method should be adopted for members for whom “the estimated cost of calculating and implementing Methods A to D is the same as or greater than the projected additional benefits” to which they would then be entitled.

Members with any questions on this Newsletter should contact the Union’s Advice Office on 01234 262868 (Choose Option1) or they can email us at 24hours@btuonline.co.uk.

Fig 1: The Methods For Equalising GMPs

What The Papers Said

Fig 2: How Do Inequalities Arise?